It’s my birthday, and we’re cancelling the 6:30 dinner reservation. It’s around that time when my dad wanders into other residents’ rooms and exhibits combative behaviour, something I’ve never witnessed. I’m no professional, but it seems Dad needs care and comfort, not more medication or police threats.

Over the past few months, my daytime calls of solace became evening support dial-ins. Then, one evening while I was at choir rehearsal, a personal support worker (PSW) called and asked me to come over because Dad was in another resident’s room. Apparently, phone calls were no longer enough.

When I arrived 10 minutes later, my dad was under the covers in his bed. The PSW handed me Dad’s pyjamas. I’ve never dressed my dad, let alone considered what it means for an aging person with dementia.

I played Dad some of his Latvian choral favourites; we talked and laughed. And Dad didn’t want to remove his clothes. Finally, after half an hour of distractions, I got Dad to brush his teeth. I felt a rush of victory.

My dictated notes from that evening conclude with the following lines. “The PSW told me that Dad switches to Latvian at night and gets tired of the staff just saying uh-huh, uh-huh. Then, he gets frustrated.”

Evening consequences

I went to visit Dad the following Monday but left by 6:15. I had limited comprehension of evenings and consequences, and it turned out that within the next hour, Dad became difficult, and the police were called. Next time, the caregivers said, Dad will be taken away.

On Tuesday, an emergency call had me back at Dad’s retirement residence. I’ll skip over the details of what it takes to move an 86-year-old knocked-out man into a wheelchair and down the hallway.

I played music and talked but received only the slightest indication that it made any difference. But because of a surprising medical experience, I knew it did.

Breaking me open

In September, I went for a second frozen shoulder procedure, which involved anesthesia, cortisone and saline injections, and physical manipulation. Maybe it was memories of the excruciating pain I experienced the first time, but I soon lost consciousness.

It was terrifying. I had no idea what was happening or why. The physician gave me oxygen and covered me with a blanket. I couldn’t talk or move, and my mind was a muddle.

But there were elements that helped me and provided unexpected insight into my dad’s dementia.

I remember a hand on my shoulder and soothing words. The overwhelming and powerful effect of music. My desperate attempt to name a song and my inability to express words or thoughts or understand what anyone was saying.

For some reason (I attribute it to my journalistic tendencies), I needed to keep the medical team apprised of what was happening. My toes are freezing, I’d say. I’m twitching.

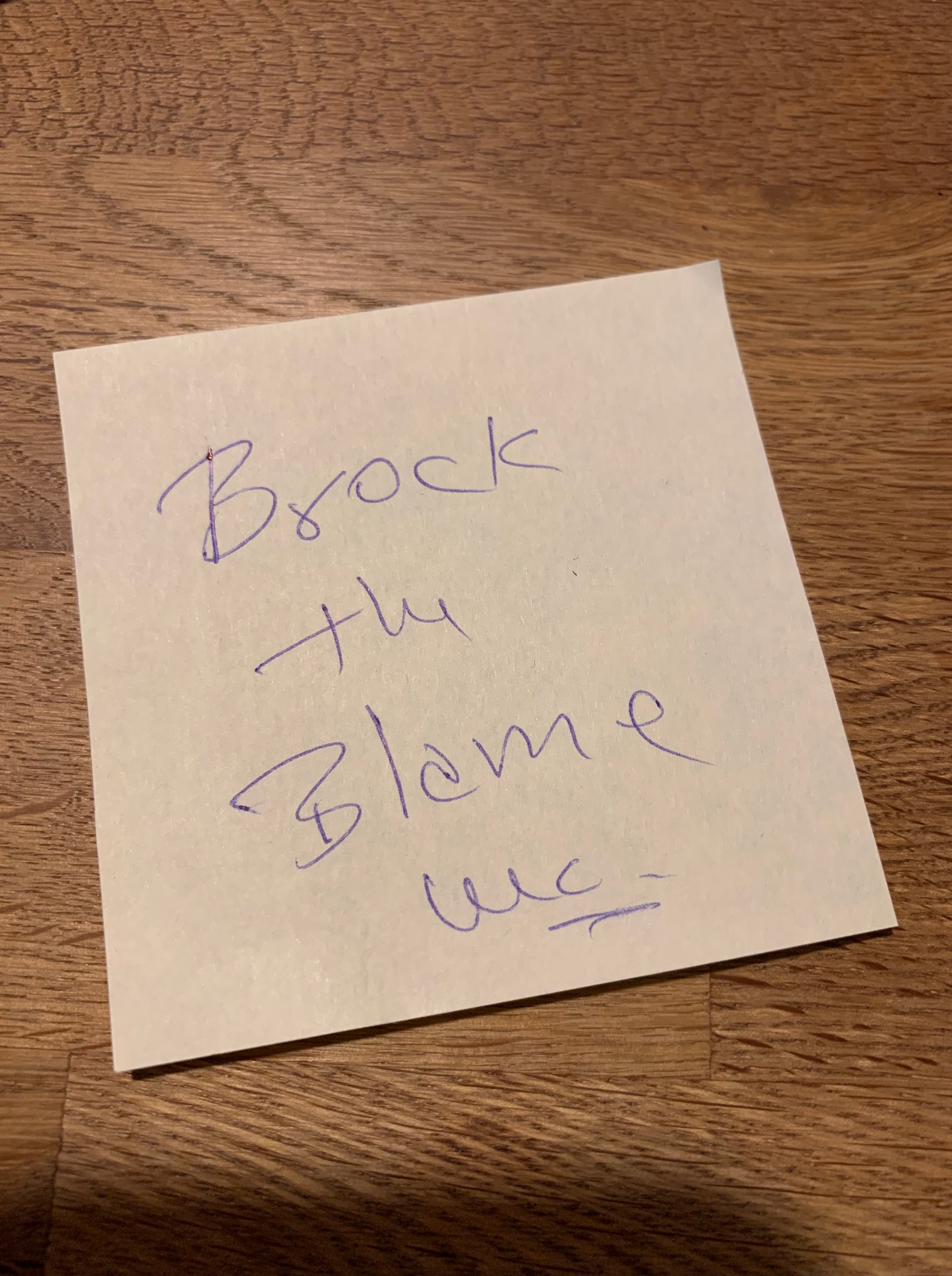

I botched my words. “Block the brain” became “brock the blame.” (The anesthetist wrote it down; I have proof.) I was aware of three parallel realities but unable to sort out how to access them.

When the whole thing was over and I got down from my high, I knew I’d learned something powerful. I’d had a little glimpse into my dad’s brain.

Weaving nights of togetherness

I’ve been attending to my dad in the evenings for almost two weeks now. Sometimes, I go early, and we have dinner together in the main dining room. At other times, I arrive as everyone on the memory floor is being rolled off to sleep.

My dad’s still strong and mobile and likes to talk—in Latvian. As I’ve learned, those are liabilities in a 21st-century ageist world.

When I arrive, Dad jumps into the fragmented storytelling that’s so familiar to me. I wait for gems that bind and emotions that often feel like they’ll break us.

Every evening is different. Sometimes, Dad sings along to the music; on Sunday, he cried in anguish. On Monday, Dad was calm but unfocused. On Wednesday, he listened silently and reached to caress my face when I said, “Arlabunakti. Es tagad iešu mājās.”*

On Tuesday, Dad and I took a selfie by the bathroom mirror. I feel a sense of accomplishment for getting Dad through the dressing phase. I think Dad’s happy because he knows the next ritual stage involves listening to music.

Initially, that paragraph was followed by the words “but I’ll never really know.”

However, last night, Dad took the little red Bluetooth speaker from my hands and held it up to my right ear, then right eye, left eye, and left ear, and I knew.

Dad gets it. The music’s a gift, and so are these evenings.

*Good night. I’m going home now.

Skaisti ❤️

Paldies, Margita. ❤️

For those struggling to understand the inside story of dementia, I highly recommend viewing “The father” – 2020 film with Anthony Hopkins

You’re getting it right, Mara. Keep learning and sharing. It’s about living in the moment that HE’S in. Keep connecting with the musical and emotional parts of the brain. The oldest and most powerful memories are where he lives… the Latvian experiences in early life shaped his neural pathways from infancy. At the end of the day when he’s most tired and wondering about where his familiar family conversations and mealtime routines have gone, you’re there. That’s what he needs.

I haven’t seen the film yet, but can’t forget the Coal Mine theatre’s production a few years ago. So painful and yet bang on.

I love this powerful description from the Globe & Mail review:

“Zeller does not let us sit back to watch a play about dementia but rather forces us to experience its mental dislocations ourselves… [He] has created a play where we both observe and experience the effects of dementia. By forcing us to experience the confusions that André experiences he endows the audience with a greater understanding of André’s condition.”

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/theatre-and-performance/reviews/article-review-the-father-is-a-fearless-portrayal-of-age-caused-dementia/

the gift of deep attention

truly. ❤️ thanks for your insightful comment.